|

Leaves: A Remembrance

Eric Rhein Talks to A&U's Lester Strong About Art as a Means of Transcendence

When one enters the world of Eric Rhein's wire drawings, one enters a realm at once simple and complex,

stark but beautiful, physically almost austere yet conceptually and spiritually rich. "Exquisitely wrought . . .

seductive but disturbing," in the words of New York Times art critic Holland Cotter, his art teases viewers with

hints of something not quite spoken yet glaringly obvious."

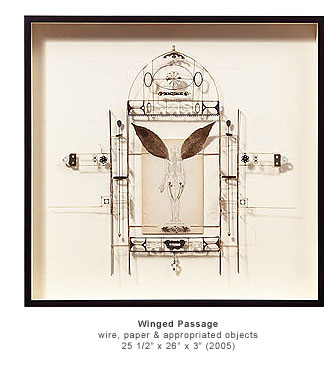

Working with the precision of a jeweler, Rhein constructs his art from wire, paper, and appropriated objects

in order to "explore the delicate and powerful connections among humans, nature, and the spiritual world," he

has written in an artist's statement. He also uses his art to explore the experience of living with HIV. Born

in Kentucky, but based in New York City for many years, his work has been shown not just in New York, but in

locations as diverse as London, Paris, Munich, Stockholm, Tokyo, and Portland. To commemorate World AIDS Day

this year, his Leaf Project, which pays tribute to people he's known that died of complications from AIDS,

is on display in New York again December 1, 2005 to January 3, 2006, in a show titled Leaves, at the Frieda

and Roy Furman Gallery of the Walter Reade Theater, Lincoln Center. Working with the precision of a jeweler, Rhein constructs his art from wire, paper, and appropriated objects

in order to "explore the delicate and powerful connections among humans, nature, and the spiritual world," he

has written in an artist's statement. He also uses his art to explore the experience of living with HIV. Born

in Kentucky, but based in New York City for many years, his work has been shown not just in New York, but in

locations as diverse as London, Paris, Munich, Stockholm, Tokyo, and Portland. To commemorate World AIDS Day

this year, his Leaf Project, which pays tribute to people he's known that died of complications from AIDS,

is on display in New York again December 1, 2005 to January 3, 2006, in a show titled Leaves, at the Frieda

and Roy Furman Gallery of the Walter Reade Theater, Lincoln Center.

Interviewed recently at his studio about the exhibit, Rhein discussed his art and some of the issues it explores.

Lester Strong: Your art is in one way very sensual, yet in another quite austere, even conceptual. How do you come by your ideas?

Eric Rhein: Art-making for me is not primarily an intellectual process. Since childhood, it has been a kind

of mirror and sounding-board for my experience. It's like something comes through me to express what I've been going

through rather than me thinking about what I've gone through and then searching for a way to express it. At its best,

making art is a sort of communion and communication with a source outside myself. I'm the vehicle for something to happen.

How did your Leaf Project happen?

I found out I was HIV-positive in 1987, when I was 27 years old, and my health remained relatively stable until 1993.

By 1995, I was dealing with systemic candidiasis, which was playing havoc with my system. It was even in my bone marrow,

causing all my blood work to plummet, including my platelets. My doctor advised me not to go out much because if I fell

I could hemorrhage. I spent most of Christmas that year in my doctor's office receiving IV drips of amphotericin B-not

a pleasant experience, but effective for me in treating the candidiasis.

In early 1996, I became part of a study involving the protease inhibitor Crixivan. I wasn't told if I was actually on

the drug or on a placebo, but it became obvious I was taking the drug when my blood work and health in general began

improving very, very rapidly. By that fall, I was feeling well enough to accept a residency at the McDowell artists'

colony in New Hampshire.

One beautiful autumn day I was out walking. The New England foliage in all its fall colors surrounded me, and

I was experiencing a sense of rebirth, feeling profoundly grateful for my returning health. As I walked, I

started to pick up fallen leaves. I sensed the spirit of friends around me, people who were no longer in their

bodies because they hadn't survived the epidemic. That's when the inspiration of drawing leaves with wire,

each one commemorating a friend who had died of AIDS, came to me. I wasn't looking for this project-it found me.

Everything I see on your walls incorporates wire, but not everything is in the form of leaves.

I've created a number of series. There's the Medicinal Garden Series, which is constructed from wire and appropriated

objects juxtaposed over prints of medicinal plants, from a nineteenth century medical book. Additionally there are hummingbirds,

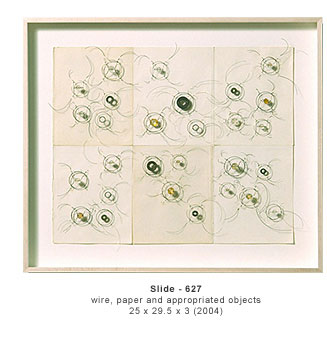

and male nudes that include anthropomorphic men and self-portraits. Currently, I'm excited about a renewed dialogue with

abstraction stemming from a series called Bloodworks, wire circles suspending discarded crystals from chandeliers and bits

of hardware, that evoke references to cellular biology and quantum physics. For the show at Lincoln Center commemorating

World AIDS Day, it seemed that exhibiting work from my Leaf Project was most appropriate. I've created a number of series. There's the Medicinal Garden Series, which is constructed from wire and appropriated

objects juxtaposed over prints of medicinal plants, from a nineteenth century medical book. Additionally there are hummingbirds,

and male nudes that include anthropomorphic men and self-portraits. Currently, I'm excited about a renewed dialogue with

abstraction stemming from a series called Bloodworks, wire circles suspending discarded crystals from chandeliers and bits

of hardware, that evoke references to cellular biology and quantum physics. For the show at Lincoln Center commemorating

World AIDS Day, it seemed that exhibiting work from my Leaf Project was most appropriate.

Do you have a philosophy of art?

I think art is the experience of making art. The object that results is a manifestation or trapping of that experience.

One doesn't necessarily have to make something to have the experience of art. It can be in one's interactions with life.

Also, I'm sure my use of wire and appropriated objects is related to the Appalachian crafts heritage that has come to me through

my Kentucky background. But my work isn't just decorative. It has a transcendent quality to it. I've been told it has that quality by

others, and feeling a connection with the sense of transcendence is a large part of what motivates me as an artist.

Is there a philosophy behind your Leaf Project?

You know, recovering my health after what I went through was exhilarating, but also perplexing and challenging. Most of

the community of friends I'd built up over the years were no longer alive. The friends who didn't have AIDS but had supported

me during the worst years of my illness sometimes didn't know how to relate to me as a healthy person. So I also felt displaced.

The part of my art relating to AIDS is my contribution to AIDS activism. It's a way of dealing with loss and continuation,

a way of carrying on and continuing an experience with people I've known who are no longer physically present, of carrying on

and continuing with myself as a changed person. I hope it helps others do the same.

(This article appeared in the December 2005 issue of A&U Magazine.)

(Back to list of Articles & Reviews)

|