| |

The Course of His Life

Reflecting fellow AIDS activist Douglas Crimp's call for "mourning and militancy," New York-based artist Eric Rhein proves art's ability to act as both a memorial and a means of activism. Through his poetic and ethereal work, Rhein explores multiple facets of the ongoing HIV/AIDS crisis from personal losses of friends and lovers to the wider decimation of New York's art and LGBT community to his own experiences as a long-term survivor. Rhein's art not only confronts the traumatic history of the crisis, but also opens an essential dialogue about the current and future realities of HIV/AIDS.

Visiting Rhein's apartment in the East Village where Rhein has lived since his arrival in New York in 1980, I explored his art-filled space including a 1981 photograph by Geoff Spear of trans artist Greer Lankton—her hair adorned with a wearable hair sculpture made by Rhein—and paintings by Luis Frangella. Speaking to Rhein, we discussed the progression of his artwork since his diagnosis, his seminal Leaves piece and the familial inspiration behind his artistic activism. Visiting Rhein's apartment in the East Village where Rhein has lived since his arrival in New York in 1980, I explored his art-filled space including a 1981 photograph by Geoff Spear of trans artist Greer Lankton—her hair adorned with a wearable hair sculpture made by Rhein—and paintings by Luis Frangella. Speaking to Rhein, we discussed the progression of his artwork since his diagnosis, his seminal Leaves piece and the familial inspiration behind his artistic activism.

As shown in his recent solo exhibition The Course of My Life at Johnson & Johnson Headquarters, which traced the trajectory of Rhein's life and career since his diagnosis with HIV in 1987, Rhein's artwork evolved after his diagnosis, mirroring the transition in his own life. Rhein's intricate sculptural chest-piece R.O.T.C., modeled after the dimensions of his own body, represents the intermediary link between Rhein's artistic life before and after his diagnosis at 27-years old. "I actually think I had done this piece prior to testing positive. In a way, retrospectively, I had a sixth sense that a transformation was about to happen," reveals Rhein.

While Rhein admits he was hesitant to disclose his positive status early after his diagnosis, he began to use his artwork as a public examination of illness, loss and his own ideas of spirituality, linked to his alternative approach to healing. Employing materials as varied as wire, found books, jewelry, hardware and photography, Rhein's multidisciplinary artwork investigates the HIV/AIDS crisis through the transcendental and metaphysical relation of the body to nature.

Rhein's art presents a stable of reoccurring imagery, specifically chosen for their rich metaphorical meanings. Even though, for Rhein, many of these symbols come intuitively, he explains that later he considers their multiple connections to his experiences. For example, Rhein's hummingbirds suggest references as varied as the Aztecs' belief that hummingbirds were reincarnations of warriors, the connection between a hummingbird's weight at 21 grams and the weight the body loses immediately after death and more simply, his mother's hummingbird feeder.

Featuring his most frequently used symbol—the leaf, perhaps Rhein's most iconic and poignant artwork is his ongoing Leaves piece, an overwhelming portrait of friends, lovers and other important figures who passed away from complications with AIDS through unique wire leaves. Started in 1996, Leaves has grown to over 200 individual leaf portraits with the most recent completed in 2014.

Rhein conceived of Leaves during a near-miraculous transformation back to health after entering a study for the protease inhibitors, which have since rendered his viral load undetectable. Reflecting on the beginning of Leaves in the fall at The MacDowell Colony, a prominent art colony in New Hampshire, Rhein states, "Before I wouldn't have been able to go [to MacDowell] because I was so ill and deteriorated. I had 4 T-cells, I was 127 pounds and I had candidiasis in my bone marrow. By the time I got there—because I was fortunate enough to get into the study for the protease inhibitors, I had a really rapid return. It was obvious that I was on this medication because I had transformed. By the time I went to MacDowell, I was in this state of bliss and light."

Collecting fallen leaves, Rhein felt the presence of his late loved ones surrounding him in relation to individual leaves. Tracing each leaf in wire, Rhein constructs a permanent personal memorial to those who died, titling each leaf with the person's first name and "some poetic reference or attribute." From photographer Robert Mapplethrope's Mysterious Robert to Fair Pam, who was in a support group with Rhein at Friends In Deed, to activist Spencer Cox's Life Altering Spencer, which will be featured in the anticipated national exhibition Art AIDS America opening at Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in June, Leaves ranges from the renowned to lesser-known individuals who were no less influential in Rhein's life. "In keeping with my desire to have the piece as an egalitarian presentation," says Rhein. "I don't single out noted people from people who were making differences in their lives in other ways besides being on a Wikipedia page."

Asked how he assigns the type of leaf to each subject, Rhein responds, "It's intuitive. It's not about the species except for some instances." Using artist Frank Moore's portrait Frank the Visionkeeper as "a broad handsome oak leaf with some instances of decay" as an example, Rhein remembers "I first met Frank in 1994 and was taken to his loft to be part of the dialogue of how Visual AIDS could evolve itself to giving hands-on support to artists. David Hirsch took me there that evening with a handful of artists, activists and arts administrators. Through that introduction to Frank and becoming more involved with helping the archive—seeing him through the years, he maintained his extreme generosity and support. There's also an interconnectedness with our work. So that happens to correspond with him being an oak—a strong nurturing figure connected to nature."

Always understanding Leaves as an activist project, Rhein has exhibited Leaves widely including in U.S. Embassies in Cameroon, Malta and currently, Austria, opening a dialogue about HIV/AIDS and LGBT issues globally. "Since I started it at MacDowell in 1996," asserts Rhein, "I wanted for the piece to be able to go out into the world as an extension of myself and the people I was honoring. They would energetically connect with the world and also give aesthetic pleasure. When people would know what they were about, it could be an activist piece."

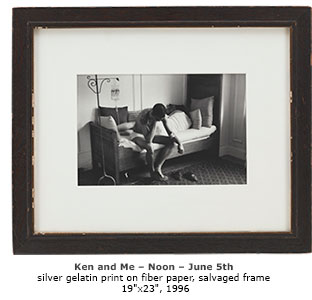

While the vastness and visibility of Leaves occasionally threatens to overshadow the rest of Rhein's insightful body of work, his compelling photographs also record his and his loved ones' experiences with HIV/AIDS, sexuality and his own identity as a long-term survivor. In his stunning photograph Ken and Me - Noon - June 5th, Rhein documents an intimate somber portrait of caretaking and illness, capturing his friend Ken in Rhein's apartment. Rhein remembers, "It was the summer that the protease inhibitors were transforming me into health while his health was declining. He was eventually able to get into a study. At that moment in time, I was helping him keep going until we both got on better footing."

While the vastness and visibility of Leaves occasionally threatens to overshadow the rest of Rhein's insightful body of work, his compelling photographs also record his and his loved ones' experiences with HIV/AIDS, sexuality and his own identity as a long-term survivor. In his stunning photograph Ken and Me - Noon - June 5th, Rhein documents an intimate somber portrait of caretaking and illness, capturing his friend Ken in Rhein's apartment. Rhein remembers, "It was the summer that the protease inhibitors were transforming me into health while his health was declining. He was eventually able to get into a study. At that moment in time, I was helping him keep going until we both got on better footing."

Playing an essential role as both a setting for his photographs and a location of significance while coming to terms with life as a long-term survivor, Fire Island appears frequently in many of Rhein's contemplative photographs such as Visitation, which depicts the monarch butterflies' September migration onto Fire Island. "For me, going to Fire Island was this interrelation of a lot of different elements," recalls Rhein. "Being able to explore socializing with a group of men as a transformed physical person, I was being greeted very much on a physical level where I wouldn't have been when I was sick. Also knowing that a lot of other men there had experienced the same thing even though it wasn't necessarily being talked about. I was alone in some way because people weren't really sharing it—only sporadically and individually. But I could also go out into nature."

Even though much of Rhein's activist tendencies certainly originate from his own experiences with HIV/AIDS, Rhein also credits his uncle Elijah "Lige" Clarke as an immensely important figure in his conception of activism whose strength Rhein honors in his delicate construction Uncle Lige's Sword. A former US private assigned to the Pentagon, Clarke was an early gay rights activist who, with his partner Jack Nichols, co-founded Washington DC's Mattachine Society and published the first national gay magazine GAY.

While Clarke was killed in Mexico when Rhein was 13-years old, Rhein's vivid memories of his uncle and his discovery of his uncle and Nichols' books I Have More Fun With You Than Anybody and Roommates Can't Always Be Lovers at eleven or twelve in his mother's cedar chest greatly influenced his view of activism. Rhein observes, "Finding them and reading them under my covers with a flashlight was my indoctrination into possibilities."

Opening an intergenerational dialogue about HIV/AIDS between long-term survivors and younger generations of activists, Rhein's work raises the possibility of art as a living and ever-evolving archive. Understanding his art as an ongoing record of his life, Rhein describes, "Art is really the experience of life and the artwork is an artifact from these experiences. I think of art as an indication of that experience and continue layering and creating, re-having a dialogue with it."

Emily Colucci

POZ Magazine

January 30, 2015

(Back to list of Articles & Reviews)

|

|

|