| |

Eric Rhein: AIDS and The Hummingbird's Warrior

One of the most beautiful art experiences I know of in the New York area is completely free, in a gorgeous, amazingly comfortable setting, and will be on display until January 31, 2015. It is of the captivating, sometimes lighter than air, other times heavy as mortality, art of Eric Rhein. The show is called "The Course of My Life," and it was assembled to be part of World AIDS Day, 2014. The catch is that it is in the lobby at the Johnson & Johnson headquarters in New Brunswick, New Jersey, an hour's trip on Jersey Railroad from Penn Station, and you do need to make an appointment to see it.

Illness, like war, has long been a powerful engine in the drama of human life. Both activities cause normal activities to halt, but illness, even more than war, rips through the masks, repressions, and rituals of daily living to plunge directly into our deepest, most spiritual feelings. Because of this, through most of the nineteenth century a cult of illness and early death arose in Europe to counter the inhibitions of the rising middle class, spurred on by the explosion of mass media through newspapers, pulp novels, and popular theater. Fashionable women modeling themselves on Elizabeth Barrett Browning wanted to look like invalid heroines—ethereal, ghost white, verging on helpless. Young men in tribute to the brief, brilliant life of John Keats, in a nineteenth century version of "heroin-chic," starved themselves to bird-beak thinness, and went out in wrinkled, bed-fresh clothing to look like romantic poets en route to dying young. In Dostoevsky's The Idiot, Ippolit, a tubercular, dying young man, is charged with telling the inconvenient truth, crashing through barriers of politeness, financial intimidation, and middle-class morality. He is also more than capable of manipulating people through guilt—because life-and-death illness is difficult to turn away from. Illness, like war, has long been a powerful engine in the drama of human life. Both activities cause normal activities to halt, but illness, even more than war, rips through the masks, repressions, and rituals of daily living to plunge directly into our deepest, most spiritual feelings. Because of this, through most of the nineteenth century a cult of illness and early death arose in Europe to counter the inhibitions of the rising middle class, spurred on by the explosion of mass media through newspapers, pulp novels, and popular theater. Fashionable women modeling themselves on Elizabeth Barrett Browning wanted to look like invalid heroines—ethereal, ghost white, verging on helpless. Young men in tribute to the brief, brilliant life of John Keats, in a nineteenth century version of "heroin-chic," starved themselves to bird-beak thinness, and went out in wrinkled, bed-fresh clothing to look like romantic poets en route to dying young. In Dostoevsky's The Idiot, Ippolit, a tubercular, dying young man, is charged with telling the inconvenient truth, crashing through barriers of politeness, financial intimidation, and middle-class morality. He is also more than capable of manipulating people through guilt—because life-and-death illness is difficult to turn away from.

By the time AIDS first appeared in the U.S., the cult of illness was long gone; it was completely counter to twentieth century America, the land of muscular independence and self reliance. It was also the place where having a genuine private life was disappearing as a business life triumphed. AIDS was shattering: it was a "private," unspeakable illness brought on for the most part sexually. It was also found almost exclusively among the country's most marginalized, least honored groups of people: homosexual or bisexual men, women of color, and intravenous drug addicts. These were people who for the most part American political society thought should be invisible and expendable.

What American political society did not count on was that AIDS would bring about another cult of illness, though not that far from the earlier one that threaded its way through repressive nineteenth century Europe: a cult of truth in the face of indifference and lies. As the young men and women of Act Up, a radical AIDS organization of the 1980s and 1990s, chanted: "Silence Equals Death!"

Eric Rhein, born in 1961, was diagnosed with AIDS in 1987, at the age of 27, after his doctor suggested he take the recently developed HIV test since he noticed that Rhein's platelet count was down. In those days results took two weeks. In the meantime Rhein, his mother, and boyfriend Mats, went to Europe for a two-week vacation, knowing all along that when they came back his test results would be in. On return, he was diagnosed with AIDS, basically a death sentence at that point. He was hospitalized several times as a young man with several intense opportunistic diseases, the result of having his T-cells and immune system ravaged by the HIV virus.

Eric's story is interesting, if not unique, both as an artist and as a man who has been living with HIV for the majority of his life, but it is equally fascinating in that he came from a singular background, making Eric and his work front-row witnesses to some of the great changes in American life. Eric's maternal uncle was Lige Clarke, a man he was close to as a boy until Lige's murder by bandits in Mexico in February of 1975. For a space of several years, from the late 1960s through the early 1970s, Lige and his partner Jack Nichols, the co-founder with Frank Kameny of the Mattachine Society of Washington, DC, were the most famous gay couple in the world. They were virtually the popular media face of gay liberation. Both were extremely handsome, trim, tall, hip-looking men who were able to grab the media's attention when even using gay to mean homosexually-oriented was still basically taboo in mainstream America. Jack and Lige were glamorous figures seen everywhere: on TV shows and radio interviews, in dozens of magazine and newspaper pieces, at demonstrations and high-society parties. They went on to found "Gay," the first newspaper of its sort to be distributed openly on newsstands, published by Al Goldstein, the controversial but very successful publisher of "Screw."

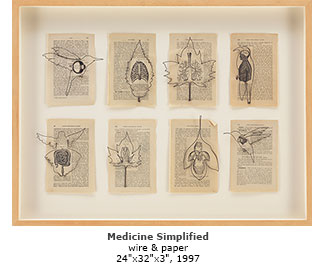

I became acquainted with Rhein and his work when I met him and his mother, Lige Clark's sister Shelbiana, at a memorial service for Jack Nichols that I produced at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Community Center in New York in 2005. His mother introduced herself to me, and then her son who was shy with an ingrained, slight hesitation when he speaks. I started seeing Eric's work often, was sometimes puzzled by it—there are times when it needs some decoding—yet always struck by its elegance and seductive, steady inward pervasiveness: it reaches inside you in ways that much of the art that either does (or attempts) to deal with HIV does not. It is hard to categorize. It is visual, and yet extremely literary—and for me as a writer that is always attractive. It is based very much on drawing, and yet there is little of what we associate with drawing in it, and often uses collage and construction techniques.

Rhein uses thin, pliant wire to "draw" in air. He does this exquisitely in his "Leaves" series: a group of now over 200 contour drawings of individual leaves done in wire, mounted against plain white paper, so that the shadow of the leaf becomes part of the effect of the work. Each leaf is a commemoration to a dead person or friend associated with the artist's life. It is apparent here we are all like leaves: individual, temporary in existence, worthy of notice, and yet part of a great whole, from a tree that is part of a system that is part of the earth's structure. Another motif in Rhein's work is the hummingbird; he is enchanted with these tough, exquisite little feathered-jewels. The Aztecs, he tells us, believed that hummingbirds contain the "reincarnated spirits of warriors." The hummingbird has become his own symbol in his own war against HIV, as he has been thrust, like so many AIDS survivors, into that Underworld of death itself—in 1995 at close to 6 feet he was down to 127 pounds, his T-cells were down to 4, his body was riddled with an aggressive candida fungus that had attacked his bone marrow, and he was told that any kind of physical activity could lead to his death. He expected to die at any moment, yet went on making art. Less than a year later, he was accepted into one of the first protease-inhibitor programs. In a Lazarus-like series of reversals from death, his life was saved, although it is not possible to credit this miracle only with medicine and chemicals.

There is something about Eric Rhein that needed to live. He has an exceptionality that transcends his physical presence. It is a pure spirit that inhabits his art—that brings, unblushingly, the large, human life-and-death narrative we so desperately want to experience directly to us. Rhein's art has made me realize that words and art are inseparable, even if the words don't exist at the moment the art is made; or that the art is only a gathering or resting place for the words, that is, the full bloom or the meaning, the experience itself, to emerge later. I find there is something very "Egyptian" about his work; it is a hieroglyphic experience—that he sees that the "word" is real, and inseparable from the image itself. Because the "word," as it is in Christian mythology, is the Spirit, the thing that lives on past us, even when the physical thing is gone. And Rhein's art beautifully poses the simple question that we all have about life and death, how do you preserve the Spirit, the elusive contours of ideas, feelings, and history that we are all about, within the also impossible, elusive, but finally recognizable contours of art?

Perry Brass

Huffington Post

December 17, 2014

(Back to list of Articles & Reviews)

|

|

|