| |

Eric Rhein: The Course of My Life

The artist reflects on nearly three decades living and working with HIV/AIDS.

"I've always been what I call a multi-media equal opportunities artist," says Eric Rhein, an artist who's been living and working in the East Village since the 1980s. "I think I came into the world with an inclination to experience and process my life through my creativity."

From wire to jewelry, pieces of paper cut from medical textbooks and fabric, Rhein's work incorporates a kaleidoscope of materials and approaches, blending the natural with the mechanical, the controlled with the untameable. Romantic relations and intimate connections blurred into a professional network that helped ensure his ability to exhibit widely, and Rhein's star was rising within a scene that continued to thrive against the confused backdrop of the mounting HIV/AIDS crisis.

The pandemic would eventually ravage the sexually liberated artistic community, decimating a generation. As members of this artistic environment were wiped out, much of their work was lost. "Unless someone was established or had someone to shepherd their work or take care of it, it would get thrown away," Rhein says, explaining that visual expressions of people's lives wound up on the streets, decaying and decomposing. From wire to jewelry, pieces of paper cut from medical textbooks and fabric, Rhein's work incorporates a kaleidoscope of materials and approaches, blending the natural with the mechanical, the controlled with the untameable. Romantic relations and intimate connections blurred into a professional network that helped ensure his ability to exhibit widely, and Rhein's star was rising within a scene that continued to thrive against the confused backdrop of the mounting HIV/AIDS crisis.

The pandemic would eventually ravage the sexually liberated artistic community, decimating a generation. As members of this artistic environment were wiped out, much of their work was lost. "Unless someone was established or had someone to shepherd their work or take care of it, it would get thrown away," Rhein says, explaining that visual expressions of people's lives wound up on the streets, decaying and decomposing.

Rhein himself was diagnosed with HIV in 1987. At the time, he recalls, there was still a lot of confusion and ignorance surrounding the disease and the ways in which it was spread. "There were discussions — not necessarily through my community of friends, but through the media — about how the knowledge of someone's status could affect their professional viability and social interactions. So when I tested positive, I didn't share with many people. In the conversation of my artwork, I wasn't comfortable being exposed with it for potential social ramifications."

At the age of 27, and still visibly healthy enough to "pass," Rhein continued his work as if nothing had changed. As someone who had always been taught to use his artistic expression as a means to better understand his own life, his identity as HIV-positive ushered in shifts in his work—veering from decorative and wearable constructions to more abstract assemblages. Through his experience at support groups such as The Healing Circle, explorations of Buddhist and Taoist belief systems began to seep into his creations. "I was processing my own consciousness of physical vulnerability and my own concept of reincarnation, of the fragility and the resilience of the spirit," he says.

Perched between a pile of books and a wooden table that, though sturdy, seems to sag beneath the weight of carefully organized stacks of paper and boxes of artwork, Rhein's face flashes with emotion as he remembers those who took chances on him. With tears in his eyes, he says that, as time has gone on, he's become better able to acknowledge the gifts of those like art dealer Holly Solomon and Connie Butler, then curator of Artists Space. "They were helping this young man," he says, pausing briefly, "who was positive, segue into the artist world he wanted to be a part of."

The momentum continued, and in 1989 he discussed his work with fashion designer Romeo Gigli in Vanity Fair. "But I felt disingenuous that I hadn't shared my status," he admits. "I even asked Connie for some advice about whether it would have an effect on the course of my career, which I'm embarrassed about now."

As time went on and his health began to decline, his status would announce itself even before he had the chance. Rhein's first showing as an openly HIV-positive artist was at the AIDS Forum at SculptureCenter in 1992. A large wire phallus — one of a number in a series that fused wire with thread, glue, and bits of jewelry — was suspended in a small room. Written on the walls was a poem he had written titled "Still":

I walk with the shadows of the men I've known, and loved, and tasted, and feel, even still, the warmth of their breath against my skin.

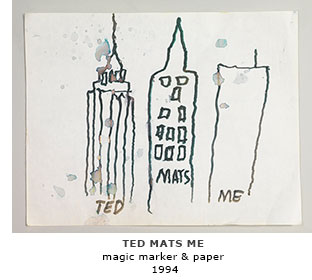

In 1994, things took a decided turn for the worse, and in the fall he ended up at St. Vincent's hospital. It was thought that HIV had entered his brain. "I went into this severe kind of manic episode that I experienced as a highly creative and enlightened state. But I was out of control," he says. "I wasn't sleeping and I was, in my case, extremely creative in bringing in all the different worlds that I was experiencing." The recollection sparks an almost palpable excitement.

Balancing himself more lightly on his chair, Rhein twists and fusses with photocopies of articles he's printed out as he continues to explain. "For a creative person, it was like a magical microcosm of possibilities, but to how we live in the tangible world, it was just dysfunctional. I was very fortunate to have a doctor, Dr. Bellman, who acknowledged that yes, this could be an enlightened state, but we had to bring [me] down to a functioning state on this level so the world could interact with [me]."  Rhein considers this time in October 1994 as his "Artist in Residence" at St. Vincent's. Provided with paper and magic markers by his mother and friend, Mats, Rhein expressed himself with an almost childlike enthusiasm as AZT was administered in an effort to help his condition. While AZT was able to successfully curtail this manic state, his health continued to rapidly deteriorate. By the end of 1995, Rhein was near death, but then he found himself on a study for the new protease inhibitors, and his health was restored.

Rhein considers this time in October 1994 as his "Artist in Residence" at St. Vincent's. Provided with paper and magic markers by his mother and friend, Mats, Rhein expressed himself with an almost childlike enthusiasm as AZT was administered in an effort to help his condition. While AZT was able to successfully curtail this manic state, his health continued to rapidly deteriorate. By the end of 1995, Rhein was near death, but then he found himself on a study for the new protease inhibitors, and his health was restored.

He had applied to The MacDowell Colony, an artists' colony, while still ill, "probably on the way out," as he describes it. By the time he went in the fall of 1996, however, he had recovered to the point where no one would know he was positive, much less so that he had very nearly lost his battle with the disease. "I walked around full of grace, and the light was different in the world, and things had different colors," he remembers. "People who met me at MacDowell thought I was in love, because of the way I smiled at everything."

It was there that he began the project for which he is perhaps best known, and one still far from complete. "I was struck by the foliage there overhead as I was transforming into this new identity, into a new person. There was a very genuine sense of the spirits of the friends who had died, like an energy field around me, as if they were helping shepherd me and acclimate me into the world as a healthy person. I started picking up leaves and recognizing them [people who had died] through shape or color or even imperfections that they had, and tracing them on large sheets of paper and identifying them."

Leaves is Rhein's way of paying tribute to those he knew and lost to HIV/AIDS. The larger exhibition, composed of many single wire leaves, each of which is some way embodies the spirit of the departed, has been shown across the world. Currently, a selection are on permanent display in the American Embassy in Vienna, Austria.

"For me, to say 'loss' doesn't work because I don't feel like they're lost: They're not. And to say that they're 'departed' is not correct either, because I still feel them with me — in thought or very often in visceral consciousness," Rhein says. "So it's an acknowledgement or expression of their existence. Unless somebody was famous, if no one speaks their name or tells their story, they're going to be forgotten. Now in the essence of things, in the larger universe, maybe that's OK. But in the world that I inhabit, I would like for them to be remembered."

It's been healing, he concludes. Not only constructing the almost 100 leaves currently in existence (out of the roughly 260 names he has listed), but all his work as an HIV-positive artist. "Survivors of the AIDS crisis who were on the brink of death and were then reborn… that can come with a sense of displacement. My Lazarus experience came here in the East Village. I actually think of it as living in a treehouse, with the trees growing outside, the old furnishings and natural palette." And sitting in his studio/apartment on a recent November afternoon, the way in which the light dances, illuminating the room with the colors of the changing leaves, it doesn't take much to imagine that we're in one, albeit a very well insulated one. "I realized that my work can be an escape from the world, and it's been somewhat challenging to perceive myself as a living, vibrant human being."

While his work allows him to remain in the company of those he's loved and known, he also believes that it helps keep him connected to the world of the living. "Through the help of organizations like Visual AIDS and the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, I'm surrounded by this group of young people in the twenties who have, thankfully, emerged and are interested not only in their own lives, but also in the history that my generation has held. And," he adds with a meaningful look at this writer in his twenties (who happens to live next door), "in them I see some of the young people I knew who died too soon."

On Dec. 1, International World AIDS Day, Rhein has an exhibition opening at the Johnson & Johnson World Headquarters, located in New Brunswick, NJ. Running through January, The Course of My Life features a selection of work created over nearly three decades living with HIV and AIDS. The pieces date from 1987, when he first tested positive, through the present day. He also intends to complete the remaining leaves and, accompanied by short biographies of the men and women remembered, present Leaves in its entirety in 2016 to commemorate 20 years since its conception.

James McDonald

OUT

December 1, 2014

(Back to list of Articles & Reviews)

|

|

|